易經

I’ve been fascinated by the I Ching for more years than I can remember. Maybe it’s having lived through the 60s and Flower Power and all that stuff, and being intrigued by some of the artistic, literary, and psychological associations like Hermann Hesse, George Harrison, and Jung; but I didn’t start looking at it more seriously until the 1990s. Since then I’ve kept taking it up and putting it down again, frustrated by its opaqueness and, quite simply, its foreignness.

And still I come back to it, and have a modest collection of different translations and books about it. I’m attracted to it not as a book of divination… who really wants to know what will happen, especially at this moment in history? It will be bad enough to find out when it actually happens. No, what appeals to me is the sense that it speaks with a voice of wisdom, a very different kind of wisdom from what we’re familiar with in the West, although often saying many of the same kind of things. It has a lot to say about how to develop moral character and right behaviour: how to study to become a better person; and I like that.

But still, much of what you find about it in books or on the Internet seems either mad, or unnecessarily esoteric, or alternatively just plain trivial. What has changed in the most recent time, has been coming across the idea that I might actually read it. (I know, I’m slow on the uptake… But the Changes don’t reveal their deep secrets to the person in a hurry. I think.)

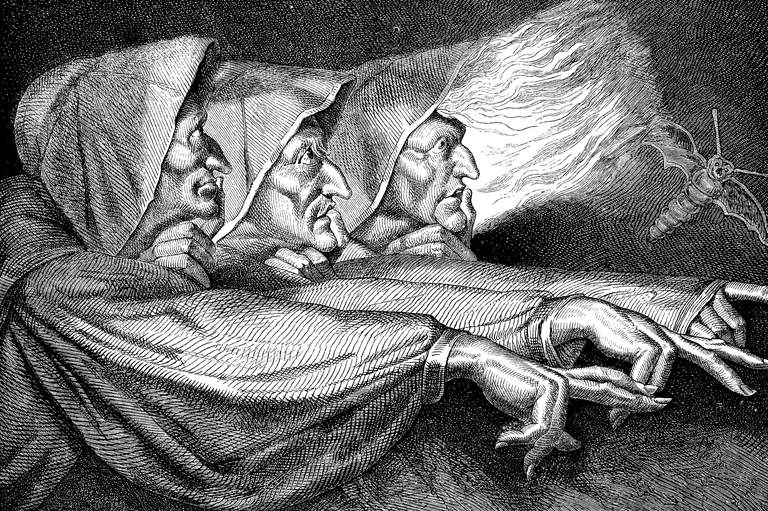

Thomas Cleary, in The Taoist I Ching, insists that you cannot make any sense of this book, if you have only a limited knowledge of it, and this is especially true of any random approach (such as, only reading the hexagrams that result from some random process, whether counting yarrow stalks or tossing coins).

“Therefore, the first step is to read the book in its entirety, without pausing to judge or question, just going along with the flow of its images and ideas. … Ancient literature suggests reading one hexagram in the morning and one at night. At this rate, this initial phase of consultation can be completed in approximately one month. This may have to be repeated one or more times at intervals to effectively set the basic program into the mind.”

In fact, on this first read through of the 64 hexagrams (Book I in the Wilhelm/Baynes version), I’m going faster than just two chapters a day; I can come back to that more leisurely approach later. But the overview is already yielding wonderful nuggets: not least the quaint old-fashioned ideas that moral character is important; that it’s especially important in people with power and influence in the state; that everyone has a responsibility to cultivate it; that things go badly for everyone when moral character is lacking – especially aomng the people in power.

Take, for example, the Image of hexagram 12, P’i / Standstill (Stagnation):

The hexagram for this is ䷋: made up of the trigrams Ch’ien, the Creative, Heaven over K’un, the Receptive, Earth. These are complementary realities, but in this particular arrangement they are pulling away from each other, rather than working together, hence the idea of Standstill or Stagnation. (Don’t worry if this is all Chinese to you: walk with me for a while.)

The text for the Image reads:

Heaven and earth do not unite:The image of STANDSTILL.Thus the superior man falls back upon his inner worthIn order to escape the difficulties.

He does not permit himself to be honored with revenue.

And the commentary begins:

When, owing to the influence of inferior men, mutual mistrust prevails in public life, fruitful activity is rendered impossible, because the fundaments are wrong.

It seems to me you could hardly find a more accurate summary of Brexit Britain, and what’s wrong with the state of our nation and politics at the present time. People have simply lost all trust in our political class because the perception is that they are morally inferior people. It used to be the case that society, schools, the whole process of education and upbringing, taught that you should regard it as a moral duty to use your skills and gifts for the general good, not just for your personal advantage. Especially if you enjoyed any kind of privilege or position: and even receiving a free secondary, let alone tertiary, education, was an enormous privilege, bringing responsibility with it. Certainly that’s one of the things were were taught at my local grammar school, even if the invisible sub-text was that we would possibly be called upon to govern the Raj (or whatever the 1960s equivalent of that was) under the supervision of the gentlemen whose privilege had been to enjoy a public (sic) school education. This is no longer the case. The antics of the entitled classes, as exemplified by the Bullingdon Club and its many wannabes, is enough proof. The popularity with the Tory Party of the unspeakable Boris Johnson, and the absurd and terrifying likelihood that he will soon be Prime Minister, confirms it.

And all the while I’m sure there are many, many people in pubic office, perhaps even in Parliament, who really do have a notion that they are there to do good and to work for the common good. It’s just that their efforts are made invisible by the greed and wealth of those among them who continue to vote for measures that oppress the poorest and most vulnerable, and make their lives a misery. Theresa May appeared to say the right things when she spoke of making Britain a country that worked for everyone, but most of the policies of her Government shouted the opposite, and much louder. Francesca Martinez spoke for many, and earned the applause she received, when she said on Question Time that the Tories have blood on their hands, because their austerity policies have been a direct cause of 130,000 deaths.

There is much more in the I Ching about how rulers in particular, and all people in general who seek to live in wise harmony with the universe, should fashion their lives. Sadly, I doubt if the Boris Johnsons of this world and all those who admire them, so much as give a damn.