In the congregation where I celebrated the Eucharist and preached this morning were two distinguished public figures and writers whom I didn’t know by sight. And whom I won’t name, for security reasons. On leaving they thanked me for my ‘brilliant’ sermon. When the churchwarden told me who they were…! That may not have been the, but it was certainly one of the high points of my ministry.

And here’s the sermon:

Living Water

We tend to take water for granted, don’t we? (In spite of the present state of Thames Water.) We turn on the tap, and water flows freely. We don’t expect to have to walk down to the end of town and fill buckets at a well, to carry home water to drink or cook with, or wash. And yet in Jesus’ time, that was the way it was done. Water — an essential of life, and a refreshment and pleasure not only to people living in arid climates — was a hard-won thing, something to be treasured and not taken for granted.

We heard in John 4.5-26 how Jesus passed through Samaria on his way from Galilee to Judaea. Samaria was roughly the area of what had been the ancient northern kingdom of Israel. It was conquered by Assyria in the 8th century B.C., and its people taken into exile. The King of Assyria then brought people from Babylon to resettle the land, and subsequently sent one of the priests who had been taken into exile, to teach these settlers the ways of the God of Israel. (Improbable? But you can read about it in 2 Kings 17.) So by the time of Jesus, the Samaritans were a mixed race (Israelite, Babylon etc), not pure-blood Jews, holding to a form of Judaism, mostly only the Torah, and of course not the ‘proper, orthodox’ Judaism of the Jerusalem Temple and authorities.

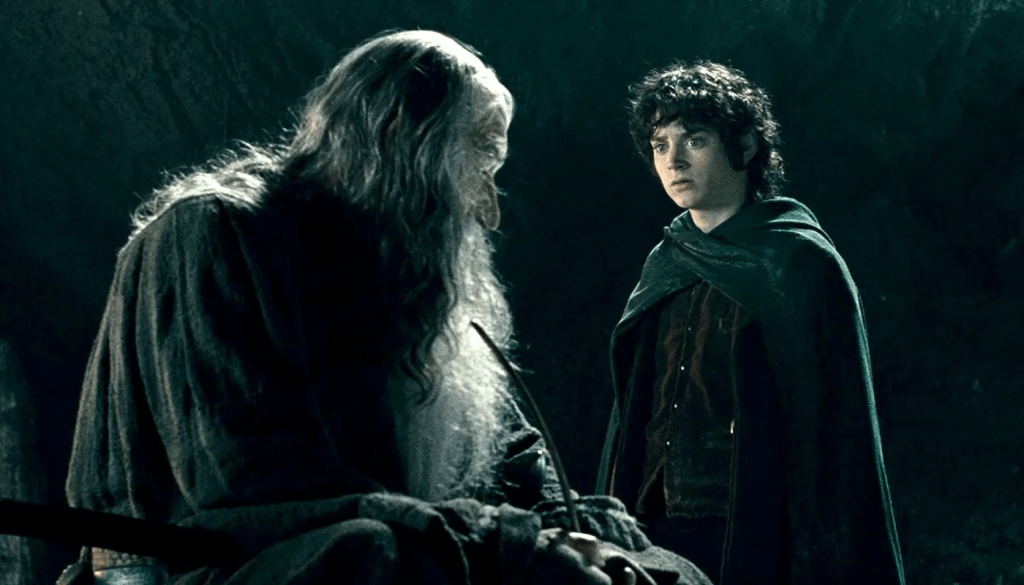

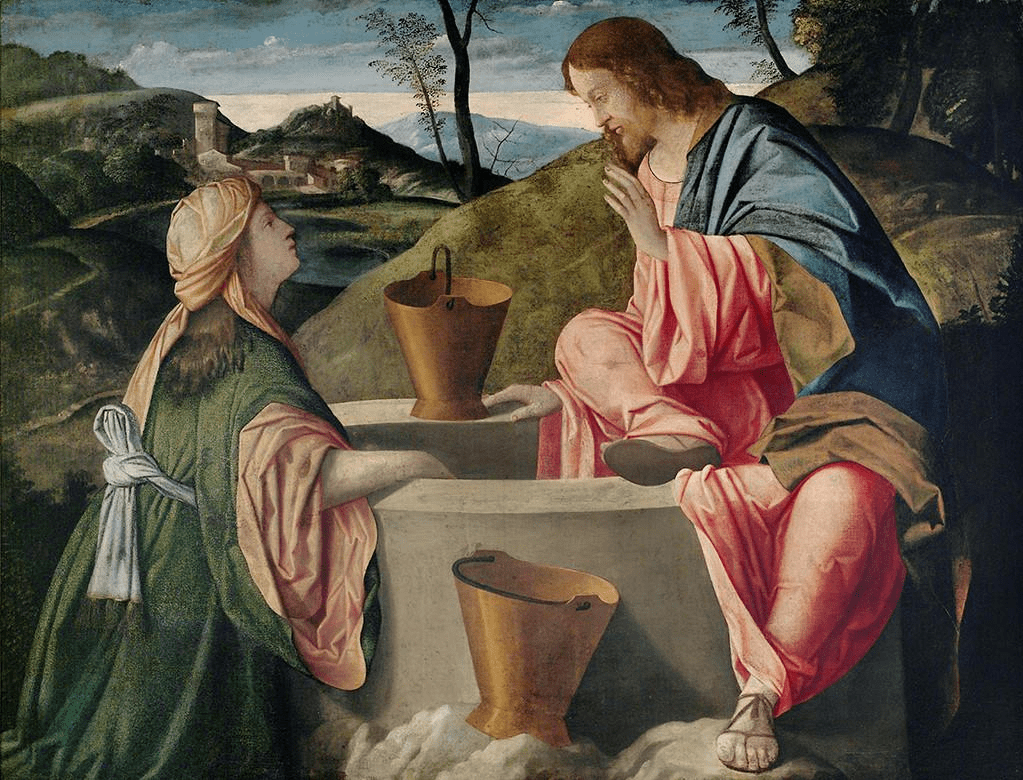

So in this setting, Jesus sat down beside Jacob’s well at noon and met this woman. It’s a great story, and one we’re so familiar with that we forget just how strange and transgressive were the things it describes. Jesus, a devout Jew, talking to a woman, a foreigner, a heretic, who furthermore had a probably disreputable personal history. This is the kind of thing, John is telling us, that the incarnate Son of God does.

And it’s interesting that Jesus doesn’t begin by denouncing the woman, or preaching to her, or telling her he’s going to save her. He asks her to do something for him, to give him something. Putting her in a position of equality or even superiority. And that allows her to be curious (Why is he, a Jew, talking to a woman, a Samaritan?) It begins the kind of conversation which happens quite often in John, where people at first don’t understand what Jesus is saying, or seem to be talking at cross purposes, until Jesus finally explains it to them and helps them to understand what he means, what he is offering, who he is.

“If you knew the gift that God is able to give, and who it is that is asking you for a drink, you would have asked him, and he would have given you living water.” And when this arouses her interest and she asks how it’s possible: “Everyone who drinks of this water will be thirsty again, but those who drink of the water that I will give them will never be thirsty.” Again: how can this be? But it has certainly got the woman interested: if she could have water like that, it would save her this daily, several-times-daily, labour of fetching water from the well.

But then it’s as if Jesus goes off at a tangent, asking her to go and bring her husband. Well, we know that’s a sore point for her, and apparently Jesus knows all about it too (how?). So she changes the subject: to religion. For religion to seem like a ‘safe’ subject, the issue of her marriage must have been a very sore point. But, Let’s talk about the differences between what we Samaritans and you Jews believe. About where and how to worship God. Here is where Jesus becomes quite dogmatic. He tells her that the Samaritans don’t know what they’re worshiping, but the Jews do, because salvation is from the Jews. They worship God in spirit and in truth, and that’s how all people must worship God.

This woman is quite a feisty character, I think she’s actually pushing back at Jesus’ telling her the Samaritans don’t know what they’re worshiping, when she says I know that Messiah is coming (who is called Christ). You see, we do believe in a coming Messiah and Saviour, just as you Jews do. And this gives Jesus the opportunity for the self-revelation that makes all the difference. Jesus said to her, I am he, the one who is speaking to you.

The I AM sayings are one of the characteristic, key points of John’s Gospel: Bread of Life, Light of the World, Good Shepherd, Resurrection and the Life, the Way, the Truth, and the Life. And I AM is the Name of God, revealed to Moses at the burning bush, when he asked God what is your name? And God replied I AM who I AM.

When Jesus says I am he, the one who is speaking to you, it’s a claim, in effect, that he himself is God in bodily human form, yes, standing there talking to her. And offering her, as he is uniquely able to, this gift of the water of life, living water, gushing up to eternal life

We are bound to connect this with what we read later in John’s Gospel, when Jesus went up to Jerusalem for the Feast of Tabernacles, and on the last day of the feast he stood up and cried out (this is John’s way of saying listen up, this saying is really important, it’s meant for everyone’s ears): “Let anyone who is thirsty come to me, and let the one who believes in me drink. As the scripture has said, Out of the believer’s heart shall flow rivers of living water.” And John adds: Now he said this about the Spirit which believers in him were to receive, for as yet there was no Spirit because Jesus was not yet glorified.

The ‘living water’ that Jesus promises is the Holy Spirit: God’s life, God’s very being, within everyone who believes. How could we imagine, or wish for, any greater thing? For this is not a promise of a few drops, but it speaks of God’s superabundant generosity: rivers of living water, gushing up to eternal life.

Lent is a time for reflecting on our spiritual health, seeking to know God better and deepen our relationship with God. What better way to do this, than to be sure we are asking for all the abundance that God desires to give us, receiving it with thankful hearts, and living in that abundance day by day?

Here we are, Lord Jesus. We come to you, we believe. Give us, we pray, that living water of the Holy Spirit which is your gift to your people. We receive it with joy, and thanks be to you, God, for your inexpressible gift!